There has been a lot written in the past year about the reduced fundraising by private asset managers and the increased amount of time they are taking to raise funds. The headlines have been that, in 2022, private funds raised 11% less than the prior year¹ and through June 2023, global fundraising declined 35% year-over-year.² These results come after extraordinary growth during the prior 10+ years. In addition to lack of growth, the average time to raise a fund has reached approximately 15.8 months which is the longest time since 2012.³

As institutional investors slow their new commitments to private assets, fund managers are looking to accelerate the growth of a relatively new market channel – individual investors – commonly referred to as the “democratization of private markets.”

Relying on our experience raising and investing private capital over the past 30 years, we discuss the primary reasons that private asset fundraising has slowed and the opportunities and challenges that it presents for individual investors.

The End of a Long Run…

Steve: According to industry sources there has been a dramatic drop-off in private fund capital raising over the last couple of years. Patrick, what is your perspective on the market today?

Patrick: The private markets industry has experienced extraordinary growth over the past 10 – 15 years and it now feels like it has reached a level of maturation where the dynamics will be different going forward.

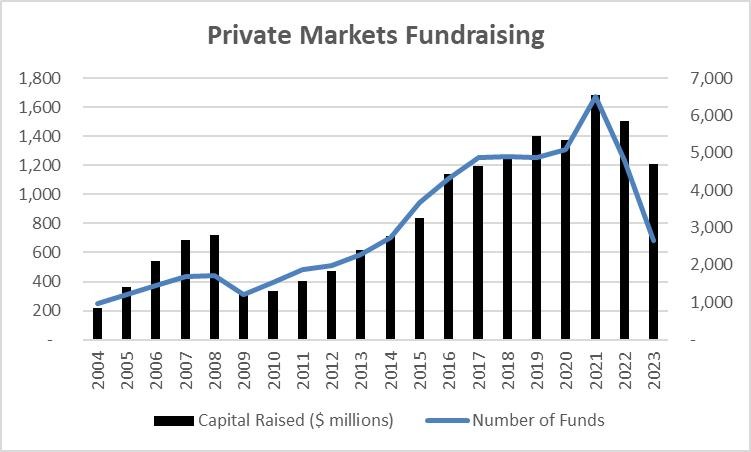

Consider that since the great financial crisis (“GFC”), private asset fundraising increased by over 300%, or 12.8% per year since 2009.⁴ The only decline during that period was in 2020, as the COVID pandemic started, but the market rebounded to a record high of almost $1.2 trillion in 2021. Absent a crisis (GFC or COVID), the decline in fundraising and private funds formed during 2022 and 2023, as shown above, is somewhat of a shock for the industry.

Steve: That is a remarkable decline – but has it been across the board for all managers, or are some faring better than others?

Patrick: No, it has not been the same for all managers, and some of the differences that we have seen may reflect broad secular changes in the industry. I would point out two in particular:

- First, larger brand name managers are taking market share. McKinsey has reported that larger funds (those defined as $5 billion or greater) increased their capital raised by 51% and smaller funds (those less than $5 billion) declined by 28%.⁵ This is a trend we often see after a dislocation as larger fund managers are often quick to react to market shifts and, in times of uncertainty, investors prefer familiar brand names. However, this shift may be more secular as greater scale is needed to cover increased deal sourcing, underwriting, compliance, and reporting costs in a maturing alternatives market.

- And second, lower-risk strategies have gained more prominence. We have seen private equity and real estate fundraising decline by double-digits while private credit and infrastructure and natural resources were able to increase their share of capital raised.⁶ Again, this shift to less risky parts of private markets may be more permanent as higher interest rates allow investors to curb their need for higher yields from alternative assets.

The “Denominator Effect”

Patrick: Steve, from the institutional investor perspective, why do you think that there has been a decline in fundraising?

Steve: Well, it definitely starts with what is called the “denominator effect.”

For a variety of risk management reasons, most institutional investors develop investment policies that set allocation guidelines for public equities, fixed income, domestic, international, etc. For institutions that have allocated substantial capital to private assets, they also often have guidelines specifying how much private assets should be as a percentage of total assets. This is primarily done to manage liquidity and the percentage is typically 5-15%, although for some it can be much higher. Historically, if an institution was at or near its target ratio for private assets as a percentage of total assets, and the public equity markets declined steeply, privates then exceeded guidelines.

For most institutional investors, the stock and bond market correction in 2022 led to a shrinking of the overall size of their portfolio. In contrast to double-digit declines for public securities, private assets were mainly flat to positive for the same period due to lagging reporting requirements and less volatility in private valuations. As a result, the amount of private assets held by many institutions significantly increased as a percentage of their total assets. In response, these institutions quickly moved to take corrective actions – i.e. slowing or stopping new commitments to private funds.

Portfolio Investment Exits Slow

Steve: Also, when capital markets slow down, realizations are slow as well. This means there is less cash coming back to portfolio managers and so less cash to reinvest.

Patrick: That’s right – most institutions have a model predicting quarterly or annual cash they expect back from their private fund managers’ realizations and when M&A volume drops like it has the past 18 months or so, they have to readjust to the new normal. This means less capital re-invested into the private illiquid part of the portfolio.

Steve: Yes, I agree. Rising interest rates and economic uncertainty have precipitated a slowdown in the pace of exits from private portfolios. The knock-on effect for investors is that, with fewer realizations from their private fund investments, there is less cash with which to make future commitments.

Time to Rebalance and Retool?

Patrick: Steve, we worked on a corporate lending fundraiser together during the GFC. We are clearly not in a crisis like that, but what is your perspective on how institutional investors look at their private asset portfolio during times of significant uncertainty?

Steve: Thankfully, the U.S. economy and the broader global economy are reasonably good right now, but we have experienced steep increases in interest rates and inflation, highly volatile equity markets, economic stress in China, and the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East – all of which fuel the concerns and fears of chief investment officers. In periods like this, CIOs are not in a rush to make significant new commitments and they may even pause making commitments.

I’ve seen another element slowing portfolio allocation over the last year and it’s more of a human resource allocation issue. On the LP side, CIOs get really focused on what they own and how to mark it when there is market volatility. You really see this now in the commercial real estate space with office and increasingly with multifamily portfolios: a real “all hands” deep dive effort by investment staff to try and figure out what they have exposure to and any potential losses they might be taking. So more of an inward focus by institutional investment staff instead of reviewing new ideas, which slows deployment into new funds.

Patrick: I agree, we saw it back in the GFC and we are seeing it today – a lot of focus and handholding on fund managers’ existing portfolios.

Reflecting on the GFC and the lending fundraiser that we worked on, I think the GFC was a turning point in the alternative fund market’s desire to pursue private credit in a big way – corporate, real estate, and infrastructure. Institutional investors re-evaluated what they wanted from their private fund portfolios, and I think we’re seeing some of this re-evaluation now in this dislocation. Investment ideas and habits can be sticky and it can take a year or two for new ideas to take hold and for investors to start to execute on them. Sort of a pause to figure out the next steps, which may be one cause of this fundraising slowdown we’ve seen.

Steve: It will be interesting to see what comes out of this market dislocation – how fund managers and investors adapt to emerging market dynamics such as generative AI, energy transition, and localization of supply chains.

Shifting Landscape

Patrick: So Steve, as large institutional investors and large private asset managers work through all that we discussed above, what guidance would you have for smaller institutions and individuals looking to participate in a market like this?

Steve: Recognizing that fundraising from its traditional sources of capital has slowed, private asset managers see a significant opportunity to tap into the $45 trillion of wealth currently held by non-institutional investors.⁷ This market dynamic also creates an opportunity for individual investors who will likely get access to a much greater number of funds through their advisors.

But many of the same issues that institutional investors grapple with in a difficult fundraising environment, plus some that are a bit more unique, apply to smaller institutions and individual investors and need to be carefully evaluated. I would highlight a few:

1. If the fund has already made investments, are they worth more or less than cost?

Virtually all closed-end funds that have already had a first closing and have started to make investments bring new investors in at cost plus an interest charge. If the fundraising process takes a long time, investors will have the benefit of being able to evaluate any investments the fund has already made, and how they are valued. Investors should consider whether they agree with the general partner’s valuations on existing fund investments and assess whether they are buying into the fund at a premium or at a discount.

2. There is a greater need to carefully track unfunded commitments and be prepared for large capital calls.

Committing to a fund later in its fundraising process, particularly if it is taking a while to complete, may result in a large initial capital call to fund investments already made by the general partner. This could also occur if the general partner uses a credit facility to make investments and waits until the end of the fundraising process to make its initial capital call.

Although most investors plan to make somewhat regular and consistent capital, be prepared for a large upfront call for funds that are in-market for a while. For investors looking to get their capital to work quickly, investing in a fund that is near or at its final close can be an effective way to do so. Also, when tracking exposure to private assets as a percentage of total assets, it is prudent to assume that all unfunded capital is drawn and no existing assets are sold which will provide a “maximum private asset exposure.”

3. If accessing a fund through a feeder vehicle, how likely will the feeder meet its fundraising target?

It is expensive for intermediaries to create and maintain feeder vehicles that aggregate individual investor commitments as a single limited partnership interest in a private fund. While some costs paid by investors are directly tied to their commitment to the fund (such as the upfront and annual management fees of the feeder), other costs are proportional to the total capital raised by the feeder vehicle.

For example, an investor committing $1 million to a feeder vehicle that expects to raise $50 million would expect to pick up 2% of the administrative costs of the feeder. This may translate into a 0.30% reduction in return. If the feeder only raises $25 million, that same $1 million commitment could pick up 4% of the feeder’s costs further reducing their return.

Investors should ask how much capital has already been raised for the feeder and what happens if the full expected amount is not raised.

Patrick: Those are good points. I would also add that it is important to go back to “first principles” and make sure that the fund strategy is right for existing market conditions. The lead time to bring a fund to market often takes over a year. If the actual fundraising process takes 1 or 2 years, investors should confirm that the strategy is still appropriate. Investors should ask questions such as: Is it a riskier strategy than the current market warrants? Is the fund targeting a sector that has moved out of favor? Even if the general partner’s historical track record is good, is their investment strategy replicable in the current environment?

Making the Democratization of Private Markets a “Win-Win” in a Tough Fundraising Environment

Patrick: Private markets are increasingly being accessed by sophisticated individual investors – it’s a democratization of the asset class that has been going on for a decade or so. Is this a good time for individual investors to commit to private assets?

Steve: I think this slowdown in institutional fundraising will accelerate growth of opportunities for individuals to fill the gap for private asset managers. Getting access to opportunities in a “hot” market can create a fear of missing out resulting in quick, not fully thought-through investment decisions. In the current “cool” market, individual investors have the time to get better educated about the funds they are considering committing to, what funds may become available in the near future, and how they want to build their private asset portfolio. Executed in this way, fund managers raise the capital they are hoping for and investors avoid unpleasant surprises and invest in funds that are most appropriate for their investment needs.

Sources

1. McKinsey & Company, “McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2023: Private markets turn down the volume,” https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-equity-and-principal-investors/our-insights/mckinseys-private-markets-annual-review. https://www.bain.com/insights/bains-2023-midyear-private-equity-update-webinar/

2. Bain & Company. (2023, July 17). “Bain’s 2023 Midyear Private Equity Update.” https://www.bain.com/insights/stuck-in-place-private-equity-midyear-report-2023/.

3. Pitchbook. (2023, December 13). Private capital fundraising timelines are getting longer and longer. https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/private-capital-sluggish-fundraising-timelines#:~:text=Private%20capital%20fundraising%20is%20taking%20longer%20than%20it,PitchBook%27s%20Q3%202023%20Global%20Private%20Market%20Fundraising%20Report (accessed 1/1/2024)

4. McKinsey & Company, “McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2023: Private markets turn down the volume,” https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-equity-and-principal-investors/our-insights/mckinseys-private-markets-annual-review.

5. IBID.

6. IBID.

7. IBID.

Important Notice: Private Markets Navigator does not provide investment advice, and the information should not be construed as such. Investing in private asset funds is risky, with potential for total loss and long-term liquidity restrictions. Read our full dislaimer.